“Go fast and take chances!” – Garry Blair

“Be swift, be safe.” – Tom Groszko

“Just remember, when you’re thinking you can’t go on, that’s it’s gorgeous and you’re one of not too many who get to be out there all day. SMILE, let that mud get in your teeth!” – Katie Oswald

I found this while I was getting ready to leave on Friday. Omen? Coincidence?

These were the pieces of advice that I carried with me into the biggest race of my life so far, the Lumberjack 100. Lumberjack is a mountain bike century race, composed of three laps of a loop in the picturesque Manistee National Forest. It is the third of thirteen rounds of the National Ultra Endurance Series, which consists of 100-mile races from New Hampshire to Utah, on some of the country’s best trail systems.

For me, Lumberjack represents much more than just a race. It is the culmination of over four years of racing, training, scheming, testing and dreaming. It has been the distant prize that has pulled me forward and upward, through crashes and injuries, through suffering and pain. It has motivated me to lift heavier, train longer, eat better and work harder than I ever would have, otherwise.

I am a big proponent of setting goals. I’ve set, met and surpassed dozens of them in the last few years, but Lumberjack was THE GOAL. It’s been on my mind since Tom mentioned it to me years ago, when I was just rediscovering mountain biking as an adult. Indeed, it was Tom who got me working on long endurance in the first place, talking me into my first Death March, partnering with me and Jason for my first 6 hour race at John Bryan State Park, and even standing by the roadside, cheering like a madman, for my first half marathon.

Time to go do the thing!

Mountains always appear larger as you approach them, and so it seemed with this goal. Although I had been diligently preparing for Lumberjack in every way I knew how, the last several days before the event were tense. I was concerned about the trail conditions, about my bike being too heavy, about my new endurance setup which included two bottles and no pack. I worried that missing Barry Roubaix, and my rough day at Big Frog, which were intended to be ramp-up races for Lumberjack, had left me inadequately trained, physically and mentally.

But there was nothing for it but to do the thing, and so I fell into my pre-event routine. I studied the trail maps and elevation profiles. I made a checklist of everything I needed to take with me. I scoured the internet for race reports of previous Lumberjacks, trying to glean intelligence from them that might prove useful on race day, or at least prepare me for what I was about to face. I have found that thorough preparation has a calming effect on my pre-race jitters, but I still only had a one-word answer when the lady at registration on Friday afternoon asked how I was:

“Terrified.”

She laughed, and tried to reassure me. She pointed over my shoulder at a girl she said had finished every Lumberjack to date, and she’d tell me I was going to do fine. The girl she pointed at was Danielle Musto, who I’d soon find out was The Queen of Lumberjack, having not only raced every edition of the event, but won more than a few. Danielle did reassure me, at registration and at breakfast the next morning, patiently answering my questions and promising that, despite a solid week of rain, the trails would be in fine shape.

I had to take her word for it. It was still raining on and off when I picked up my packet, and racers coming back in from their pre-rides were looking soggy and caked with sand. My bike is not a big fan of getting wet, and I’m not a big fan of having to service the entire drivetrain and rear suspension the night before a race, so I opted to skip the pre-ride and just get to the hotel. And anyway, the mosquitoes (official state bird of Michigan) were attacking in formation!

The rain finally relented overnight, and we were greeted by a cool, humid morning, with a stubborn gray sky that hung just over the treetops. I set out my “pit” with Brad and Simona, friends of friends that I had met at Big Frog. My “pit” consisted of one cooler full of pre-mixed bottles of Infinit and one bag of miscellaneous tools and supplies. If all went well, I’d only need the bottles, and maybe some chain lube. If it didn’t, I’d be headed back to the car for my work stand, or worse, my first aid kit.

I tend to stay pretty relaxed before the start of a race, joking with the other athletes and staying loose. But this time my smiles were a little forced, my laughs cut a little short. I finished my final checks on the bike, setting tire pressures, fixing an already-ripped eyelet on my race number and applying another liberal coat of bug spray, while the race director made a few announcements through the megaphone that I couldn’t hear. I didn’t bother with an extensive warm-up routine, figuring the opening two miles of road leading into the singletrack would suffice.

Soon the mob of riders was streaming out toward the start line, and I found my way out with them, settling into a place in the back third of the gaggle waiting at the line, in the gap that appeared between those who obviously wanted to go hard, and those who merely wanted to survive. My own ambitions fell squarely between those two, and so the gap was convenient. There were more instructions, inaudible through the pack of riders and the thick humidity, and then a siren sounded, and we were off! Hundreds of cleats clicked into pedals, and knobby tires hummed against pavement as we spun easily toward the trailhead.

ALL OF THE JITTERS!

The swift flow of riders down the road became a logjam as we entered the singletrack, but there was little complaining. Everyone knew it was going to be a long day, and so we just got to the business of pedaling, flowing through the trail in single file. Danielle’s assurances about the trail conditions were correct, and I smiled as I found the sandy soil as grippy as the trails were rhythmic. Soon we encountered a couple gentle climbs, and the pack began to spread out. I made a few passes where I could, in an effort to maintain a level of exertion that both preserved my momentum and would be sustainable throughout the day.

One of the concerns I had going into the race was my hydration and nutrition setup. I had decided to give Infinit, a custom-blended, all-inclusive drink mix, a try. The recommended consumption rate is 1 bottle per hour, which necessitated that I run with two bottles. But the frame and suspension design of my bike means that one bottle is slung under the down tube, rather than vertically on the seat tube, which is less than desirable due to the risk of the bottom bottle being shaken loose. I tested the new setup on two short rides the week prior, and had no problems with my Lezyne cages holding full bottles securely.

Those bottles were my lifeline. They contained all of the hydration and nutrition I was going to need to make it through the day. The plan was to start each lap with 2 bottles, refill both of them at the aid station at mile 17, and then swap them for the premixed bottles from my cooler at the end of each lap. I’ve struggled with dehydration and inadequate nutrition in the past, leading to muscle spasms and cramps that can make for a very miserable day.

So imagine my horror when, looking down after a series of roller-coaster hills only eight miles into the race, I looked down and saw nothing in my bottom cage! I cursed and pulled off the trail, next to a guy who was fiddling with a broken derailleur hanger. I reasoned that I couldn’t have dropped it too far back, as I had been checking on it with regularity. And I needed that bottle, and the nutrition it contained! In a panic, I made a rookie mistake, a crucial error that I’d regret for the next several hours.

I wheeled around, and headed back up the trail, looking for my lost bottle.

It was a stupid thing to do; a fool’s errand. Part of me knew that even as I was doing it. I was in a hilly portion of the course, and backtracking meant I’d have to climb those hills over again. I couldn’t even ride back, since the hundred or so riders behind me were still coming on, meaning I had to haltingly hike beside the trail, stopping to let groups of riders past. I was sure I could locate my bottle, since it was white and red against the brown and green forest floor, but as I pressed on over yet another hill, it was nowhere to be found. I walked a half mile in the wrong direction, getting passed by just about everybody, before giving up hope (or coming to my senses, more likely) and turning to rejoin the race.

Now I had compounded my problems. I had used up extra time and energy looking for a bottle I couldn’t find. I had lost touch with a pack of riders who were maintaining a pace I felt I could hold, which can be crucial to get through a race of this duration. I would have to complete my opening lap on half of the water and food I had planned, and now, I thought, I needed to go harder still to catch back up to where I should be in the race.

The errors were piling on. Having relegated myself to the back of the field with my poor decision making, I found myself in a prime position to make things worse: I was angry, I was on my bike, I had open trail ahead of me, and riders I knew I could catch and pass. The red mist descended. I dropped the hammer.

The next fifteen miles contained some of the best riding I’ve ever done. I was going fast and taking chances! Back through the roller coasters I sailed, bombing the descents and standing in the pedals to carry my momentum to the top of each rise. I caught and passed riders quickly, some of them surprised to see the rider they had only just passed going the other way. They had probably written me off as a mechanical DNF, only to have me calling “on your left!” as I slipped past them again. I looked for riders from the pack I had previously been in, naively thinking I could catch back on, and then relax a little.

It wasn’t to be. I had wasted probably twenty minutes looking for that stupid bottle, and twenty minutes is not a gap you make up in a mountain bike race. This reality was beginning to dawn on me as I reached the mid-lap aid station, where volunteers refilled my remaining bottle and sent me on my way. Still, I didn’t quite give up hope, as I was catching and passing riders with some regularity.

There is a metaphor in cycling regarding a matchbook. You start a race with a certain number of matches, and when they’re gone, you’re done. The idea is that you only burn matches when you have to, getting up a hill or sprinting to stay on a peloton, so that you have enough left to finish the race. With less than one lap complete, I was burning a whole lot of matches, and I was starting to feel it.

I caught a small cluster of riders on a twisty, flat section of trail, and grew frustrated that they were holding me up, but the trail was narrow and there was no opportunity for a safe pass. Finally the course emptied out onto a fire road, and I motored by them, pulling a guy on a hardtail 29er with me. The two of us traded pulls for the next few miles of trail and fire road before entering the final section of singletrack. My legs were burning, telling me in unmistakable language that they could not maintain the level of effort required to stay with the guy on the 29er. I had to back off.

My decision to ease up on the throttle was closely followed by the most challenging section of climbing on the course. Although the vertical ascent only totaled some three hundred feet, the segment was punctuated by a half dozen exhilarating descents, so that you ended up climbing several times that number. To be sure, I’ve seen harder climbs, particularly in West Virginia and Tennessee. The slopes weren’t impossibly steep, and they were mostly smooth trail. But I was feeling the consequences of my earlier poor decisions. Too much effort was mixing with too little nutrition to rob me of needed power.

At last I crested the final climb of the lap, and zipped down the descent to the start/finish area. I was relieved that I had survived my first lap on half of my planned intake, but still frustrated that I was far behind where I should be, and grimly determined to press on at whatever pace I could manage. I spent only a minute or so in the pit, stashing my second bottle from the cooler in my jersey pocket instead of the offending lower cage, before setting off again. I hoped that, with clear trail ahead of me and no reason to stop and turn around, I could clear this lap faster than my first, which had taken three and a half hours to complete.

That thought soon perished, as I spun up the first couple climbs. My legs were burning hard now, not recovering as they should between efforts. My knees were starting to hurt, my back was knotting up, and even my hips were starting to complain. Things were grinding to a halt quickly, and I was going deep into the pain cave. I glanced at my computer and saw that I was only 40 miles in. 40 miles! How in the world was I going to drag myself through another 60?!

My mood turned dark. I was contemplating failure in very real terms, convincing myself that there was no way I could finish the race, as things were going. My pace slowed further. I castigated myself for turning back for that damn bottle, for letting my frustration at not finding it get the best of me, and for trying to chase my way back through the field. This wasn’t supposed to be a race for me this year! I was only supposed to come out and try to finish! What was I thinking, hammering the way I did? And now look at me. Not even half way through, and burned up. I felt like I was out of matches. I started composing my apologies in my head. My explanation to my wife. My blog post on the race. All the harsh realities of my first ever DNF. By mile 48, I was done. Checked out, mentally.

I finally rolled into the aid station, convinced that I could muddle through the remainder of the lap, and then it’d be over, for me. As I arrived, the race leaders came in behind me, skidding to a stop while we mortals stood, mouths agape. Like an enclave of angels, the volunteers at the aid station all offered their help to each rider, leader or otherwise. Seeing on my face that I was having a pretty rough time of it, one volunteer refilled my bottles, while another one tried in vain to convince me to eat. He held out a plate filled with fig newtons and PB&Js like a maitre d’, but I declined. What I needed was to stop hurting. I asked if anybody had any aspirin. Another volunteer, who I’d later find out was the wife of the race organizer, came up with a bottle of ibuprofen, and, appraising my condition, shook four of them into my hand. I thanked her and the rest of the aid station angels and clipped back in, rolling down the trail for what I figured was the last time.

“Are you gonna do another lap?”

I had been caught by another rider, and together we were slogging along, our misery loving each other’s company.

“I don’t know,” I replied “I’m trying not to think that far ahead.”

“Me neither, but…” His voice trailed off. We pedaled on in silence for awhile, occasionally pulling over to let the leaders — who were already on their final lap — pass us uninhibited.

I had offered to let him past but he declined, saying he was only trying to make the cutoff, and I was pacing him well. He looked about as happy as I felt, but it was nice to not be alone. The stretch of trail after the aid station was flat and beautiful, through pine groves thick with the fresh aroma of logs recently cut by the Forest Service. I thought about my friend Katie’s words, and reminded myself to relax. I was lucky, after all, to be out here. Pedaling my bicycle through the beauty of the woods, rolling on soft turf and watching the sunlight filter through the trees. It was gorgeous, and it was time for me to smile, and let the mud get in my teeth.

The smell of the woods in summer is some of nature’s finest perfume, and coupled with the gentle terrain, it transformed me. I was catching up on my nutrition, and the ibuprofen was doing its job, taking the edge off my aching muscles and joints. The rider who had caught me and I rolled on, covering another couple miles of singletrack before hitting a section of fire road. He said he was going to stop and stretch, and I was alone again, but in a much better place, mentally. I was calmed, at peace with where I was in the race, and content to just keep going, and see what might lay ahead.

The climbs in the closing five miles of my second lap were still tough, but nowhere near as miserable as they had been the lap before. Content to take what my legs were willing to give me, I unclipped and walked when I had to, which was only a couple times. I focused on the descents, where the long travel of my bike’s suspension really shines, and bombed down them with enthusiasm. I tried to remember the sections, so that I’d know what to expect on the next lap…

Next lap? Wow, when did I start contemplating that reality?

I rolled back through the start/finish and to my pit for the last time, automatically going through the motions of restocking my jersey pockets and oiling my chain. I had known coming into this race that starting the final lap would be the hardest part. To date, the furthest I’d ever gone on my mountain bike was 65 miles. To do all that, and then set out for another lap of 33, would take all the mental fortitude I could muster. Yet somehow, when it came time to make the actual decision, it was as if it had already been made. I applied a fresh coat of bug spray, fired off a quick update to my wife, and rolled out, to the applause and cowbell-ringing of the small gathering of spectators and crew members.

A picture I wasn’t sure would ever happen.

My biggest worry when I registered for this race was making the cutoff. The rules were that, if you didn’t start your last lap by 3:30 pm, you were done. Somehow, despite all my problems on my first two laps, I had done that. By an hour. I was still doing well! Privately, I had told myself that I would be happy with any finish, happier still with a finish under twelve hours. Now, if I could maintain the average I had set, I might even finish under eleven!

My last lap was strangely serene. In most of my endurance racing experience, the end of the race is where you end up having to dig deep, where you hit your lowest lows, and where the struggle is most bitter. I usually reach a point where I’m not having fun any more, and I just want it to be over. But this was different. I had already fought through my lowest point, and the rebound of my mood allowed me to relax. Gone was the fear of the unknown; I had seen the course twice, and knew that while it was bookended with challenging climbs, the middle portion was relatively easy. My legs, though not fully recovered from my earlier abuse, were at least working again, and the pain in my back was manageable. I was even smiling now and again, enjoying the beautiful flow of Lumberjack’s trails.

To stay focused, I buried myself in the details of what I had left to do. How many miles to the aid station? When should I plan to change bottles? How long should I go before I stop to stretch? I set mile markers in my head for each of these things, using them to break the remaining distance into digestible pieces. Then I tried not to look at my computer every thirty seconds.

I stayed in the saddle and spun up the first two climbs, content with forward progress and unworried about my pace. I had abandoned use of the big ring some time ago, and found that I didn’t miss it. In fact, it seemed more efficient, since I didn’t have to wait for my clunky front derailleur to complete the shift as I started a climb. One last time through the roller coasters, and I chuckled at the mounting collection of bottles at the bottoms of the descents. Mine was around there somewhere, but I never did see it. The climbs became less frequent and severe, and soon I was at the aid station. Refueled for the final time, I thanked them all again and set off down the trail for the final leg of my first Lumberjack!

I was starting to feel confident now, but I was mindful of my late race mistakes at Big Frog, which had left me with full-body muscle cramps and a brutal crash only few miles from the end. It was time to be swift and be safe, ride smart, and keep looking after my intake all the way to the end. I planned my last bottle change, and thought of where I’d stop for a stretch before the last hilly section. And then it started, the final undulating ascent through the Udell Hills, on the other side of which was the finish! I pedaled as many of the hills as I could, stopping just twice to push the bike over the top before careening down the slopes. I made sure to keep my aggression in check on those downhills, as insurance against a tragic, late-race crash.

97, 98 miles in, and I was still having fun. I was riding loose, letting the bike do the work, hopping off roots and jumping the small rises. The last hill gave way to the last descent, and I shifted onto the big ring for the last time and crushed the pedals! I was sailing through the woods, euphoric. I streaked through the pit area, now half deserted, and across the finish line to the cheers, laughter and applause of the volunteers and racers already enjoying their celebratory pints.

Surreal. It’s still sinking in that I did this.

I finished! I made it! In my first attempt, and despite even my own expectations, I had completed a hundred-mile mountain bike race! I had survived Lumberjack, and got the finishers’ patch to prove it!

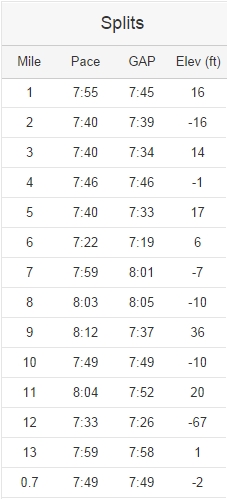

Officially, I crossed the line in 11:12:56, good enough for 169th place of 178 finishers in the Men’s Open category, and 257th of 273 overall. But given that the race sold out at 425 entrants, I’m pleased with that result, however humble! There were over 70 riders who completed one or two laps and couldn’t, or didn’t continue. I learned so much from this race, about strategy, about endurance, and about myself, that I know I can do better in the future.

And I do plan to be back! This race was so well run from end to end, the volunteers so friendly and helpful, and the course so fun, that I can’t imagine not giving it another try next year. If you’re thinking of trying out the Ultra Endurance MTB scene, Lumberjack is the place to start!