The majority of the posts on this blog have documented my successes, triumphs and progress over the past couple years. This is not one of those posts.

The majority of the posts on this blog have documented my successes, triumphs and progress over the past couple years. This is not one of those posts.

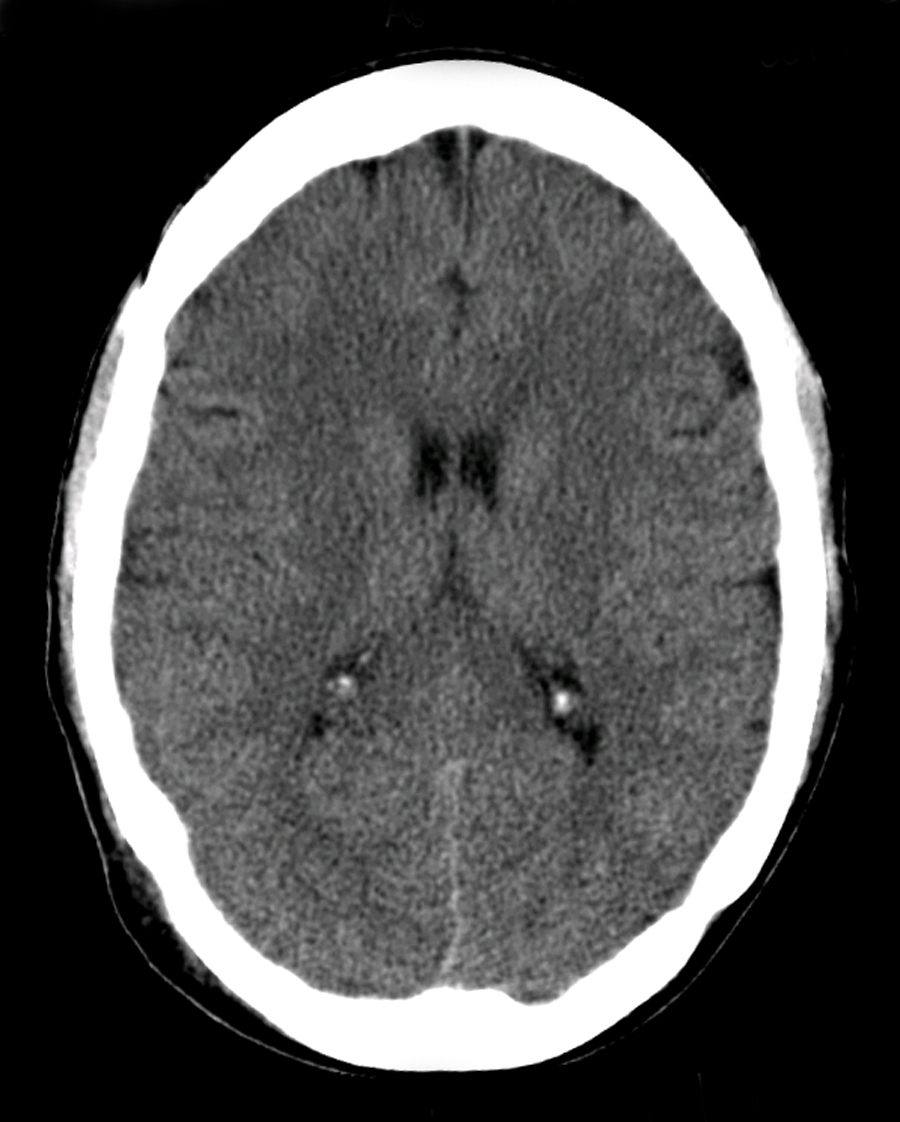

This morning at my gym, we repeated a workout from the CrossFit Open last year. It was 14.4, a chipper consisting of a 60 calorie row, 50 toes-to-bar, 40 wall-balls, 30 power cleans and 20 muscle-ups, with a 14 minute time cap. Last year, this was my first workout back after discovering the mind-crushing pain of exertion-induced, acute onset headaches. I approached it cautiously then, careful to keep my heart rate reasonable so as not to aggravate the pinched nerve that we suspect set off the headaches the week before. I finished with a score of 99, completing only 39 of the toes-to-bar before time expired.

This morning, I had it in my head that I could make it through the toes-to-bar and get to the wall balls, and provided there was enough time left, I planned to try and do all 40 of them unbroken. There was still the requirement for caution, as I’ve been nursing two very angry shoulders for the last several months, and I would need to concentrate on maintaining good scapular retraction throughout each pull to avoid aggravating them. Still, I counted on getting through them in plenty of time to attack the wall balls, and maybe even get to the bar for a few power cleans.

I didn’t make it. I failed.

I did complete three more reps than last year, giving me a score of 102, but that was small consolation. I got through the first 20 quickly enough, in bunches of five, but then the wheels started to fall off. I started missing reps, only getting three at a time, then two. With a minute to go, I reached failure, and couldn’t get my toes to touch the bar any more. I was frustrated. Dejected. Mad.

As days at the gym go, this will not be remembered as one of my favorites. But it will be important. Reaching failure is an essential element to any training program. It is the point at which the body is optimally stimulated for muscular growth. It is the benchmark against which future efforts will be measured. It can be, once the bitterness of the moment is overcome, the fuel that will drive you toward greater things. It exposes and brings into focus your weaknesses, so that you can address them with specificity and intensity before your next maximal effort.

In fact, a maximal effort is not possible without at least approaching failure. When you are striving for a personal record in any event, you are trying to reach the nexus of performance and failure. In a running race, the goal is to cross the finish line unable to run another step. In a lift, the goal is to put up enough weight that you couldn’t add another gram to the bar. On the race track, the perfect lap is one where you are just on the edge of control, using every ounce of available power and traction. In life, if you aren’t failing with some regularity, chances are you are not challenging yourself, not growing, not really living.

Before today, I never really considered failure as its own destination. I train and race hard, and flirt with failure on a regular basis, but like most people, have treated it as something to be avoided. In the ongoing battle to maintain the positive feedback loop I find necessary to keep me coming back day in and day out, I try to focus on my successes. That perspective will need revising, for me. It turns out that searching for one’s personal limits, in other words striving for failure, is the surest way to find success.

I’m not happy with how I did this morning. I did not meet my own expectations for performance. But I’ll be back to try again, having learned from the experience and improved myself in the interim. And hopefully, next time I’ll reach failure again.